23 Mar YOU’RE IN THE HOUSE! YOU’RE IN THE FIELD!: A BRIEF HISTORY OF U.S. COLORISM

“The line between colored and n****r was not always clear; subtle and telltale signs threatened to erode it, and the watch had to be constant” –The Bluest Eye –Toni Morrison

There are few Black people in the United States that are not familiar with the phrases “house slave” and “field slave.” Though they might use a more provocative word if you know what I mean. In any case, the terms are typically usually an allusion to slavery, skin color, and colorism. But what do they actually mean and where do they come from? To be clear, both light-skinned and dark-skinned enslaved persons worked inside and outside of the ‘house’ suffering unimaginable treatment. There was however, a clear and sustained preference for enslaved lighter-skinned Black people to work in the home. These stemmed from larger racist ideologies suggesting that moral character and intelligence were based on race and biologically determined. They are not. Still, lighter-skinned Black people—most often the result of rape—were deemed preferable because of their ‘white blood’. But it’s deeper than that. It’s deeper than skin. It is the combination of the social, institutional, and legal practices from slavery onward that perpetuates colorism, and continues to benefit, light-skinned Black people today.

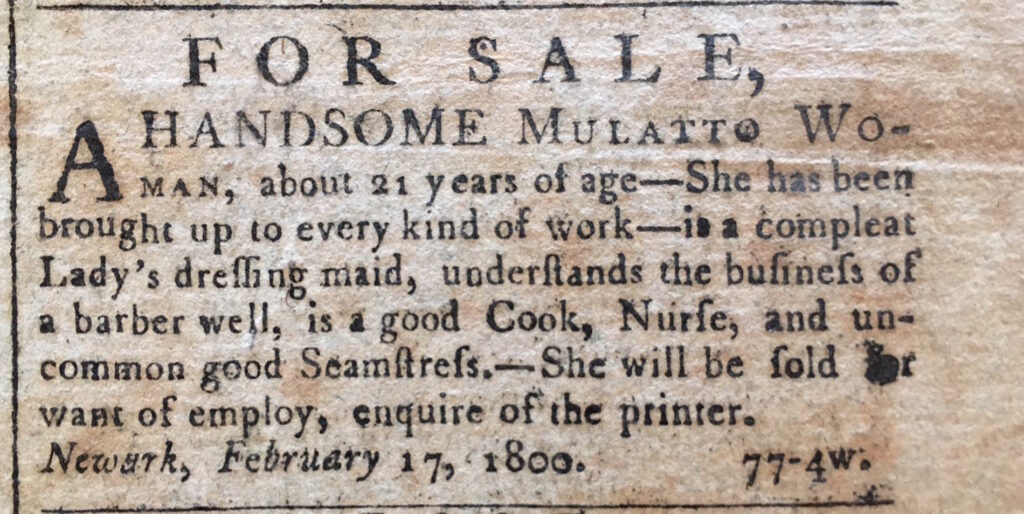

Socially, the ‘mixed’ or ‘light-skinned’ aesthetic, perceived intelligence, and associated ‘behaviors’ were deemed desirable. And, because of their perceived ‘value’, they were sometimes bought and sold at higher prices than their darker-skinned counterparts, such that owning a number of light-skinned slaves also served as a status symbol for respective plantations. Their skin color directly benefited them. Enslaved light-skinned Black people were disproportionately: placed in the home, trained in skilled labor, and taught to read. Although most time was spent in the home, field work was utilized as a means of punishment for bad behavior. The physical proximity to white people, however, proved to be beneficial. The’ extended contact with white people meant they could often perform mannerisms of the white aristocrat society. This in turn, fed into the racist beliefs that ‘white blood’ civilized Black people. In reality, however, light-skinned Black people were simply able to imitate whites more closely because they spent more time enveloped in and around whiteness.

Beyond social practices, institutional and legal customs also heavily favored light-skinned Black people and was exacerbated through the mid and late 1800s. The introduction of ‘Mulatto’ on the 1850 census as a distinct racial category from ‘Black,’ for example, marked a significant shift in the perceptions of light and dark-skinned Black people. Positive characteristics, physical, intellectual, and social among Mulattos was attributed to their mixedness. Their ties to white ancestry also meant that they were the more desirable ‘free Black’. As such, Mulattos were much more likely to be manumitted, or set free, than non-mixed Blacks were. In 1860, for example, Mulattos represented over 75% of free African descendant persons in the South and only 9% of the enslaved Black people. In the same decade, their wealth was two and half times that of free ‘Black’ persons. Once free, the trades Mulattos learned allowed them to secure relatively prestigious jobs at marginally higher rates than those recognized as ‘pure Black.’ Post-emancipation Mulattos were also busy establishing their own organizations, assuming leadership positions in freedmen’s groups, intentionally marrying other Mulattos, and excluding darker complected Black people from various social clubs.

These histories have resulted in what some have called a complexion lore—the well-known yet seldom spoken traditions of: the Blue Vein Society, Bon Ton Society, Paper Bag Tests, Brown Parties etc. Ask an elder, they’ll tell you. The ‘Blue Veiners’ as they were sometimes called, for example, formed in response to mass influx of newly freed Black persons following the Civil War. Large numbers of the Tennessee-based Blue Vein families were free before the war, and many had been free for several generations. Membership was based on skin color, not family, so long as ones ‘blue’ veins were visible on the underside of one’s wrist. The privilege is said to have offered exclusive access to night clubs, resorts, and other social gatherings. The residual effects of these communities exist today with urban cities around the country still comprised primarily of lighter-skinned Black families and organizations like Jack and Jill that promote an upper-class Black lifestyle.

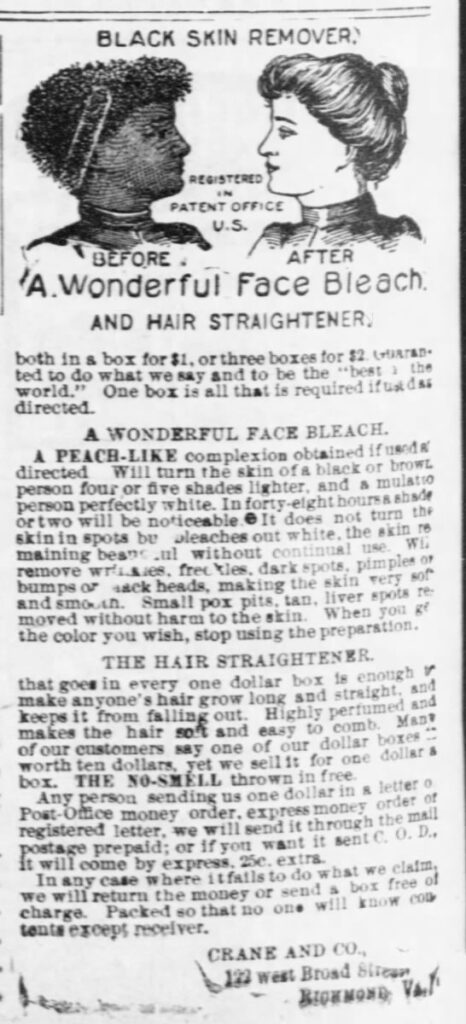

Black-owned media through the 1900s also added to colorist ideologies. Skin-lightening and hair straightening ads in popular national magazines urged Black people to alter their image. The messages were crystal clear: the ‘New Negro’ was modern, educated, well-behaved, but most importantly had straight hair and light-skin. Consider the 1902 ad in the ‘Colored American Magazine’ with a bold promise to its customers that with their product one could: “…turn the skin of black or brown person four or five shades lighter, and a mulatto person perfectly white.” Anti-black aesthetics continued despite growing Pan African and Black Power movements through the mid 1900s. In his autobiography, even beloved activist Malcolm X wrote about what he described as a strange love for getting his hair conked, or chemically straightened, before converting to Islam. That is to say, the societal pressures and subsequent benefits from conforming to colorist ideologies were pervasive and far reaching.

Taken together, the advantages afforded to light-skinned Black people by whites from slavery and post-emancipation, coupled with the colorist practices by light-skinned Black people themselves, created deeper rifts among Black communities. In other words, the social norms that already separated light-skinned and dark-skinned Black people spatially—house and field—were reinforced and created a new in broader society. Today, little has changed. We may not see the bold ads about skin lightening in Black magazines, but colorism today remains systemic and flourishes in every facet of society. The skin bleaching industry is a multi-billion dollar enterprise spreading dangerous chemicals poisoning Black bodies all over the world. Disparities in pay, education, prison sentences, media representation persist influencing how we treat each other. I invite you to think about the legacy of: being “pretty for a dark-skinned girl”; being “so articulate”; feeling “lucky to have a loose curl pattern”; preferring light-skinned partners, or being fortunate for having ‘medium’ brown skin. Or question what exactly it is are we communicating when we are claiming #TeamLightSkin and #TeamDarkSkin? Because it is these same sentiments that have and continue to keep us at odds.

Mr.K

Posted at 23:31h, 25 MarchThe false idea of a superior complexion continues to be perpetuated in pop culture and mainstream media. Many celebrities have engaged in skin bleaching and applying make up to lighten their skin tone.